Komarov Artem noted that many companies that produce hydraulic assemblies, or automotive fluid-carrying bundles, have captive tube mills. Some of these mills are now liabilities rather than assets. Pandemic-era consumers tend to drive less, and vehicle sales forecasts are way off from pre-pandemic levels. The automotive market is associated with negative words like shutdowns, severe declines, and shortages. None portend much positive change in the supply situation in the near future for automotive OEMs and their suppliers. Noteworthy is the growing presence of electric vehicles in this market which have fewer steel tubing powertrain components.

Captive tube mills typically are built from custom designs. This is an advantage in their intended purpose—making tubing for a specific application—but a disadvantage in economies of scale. As an example, consider a tube mill designed to make a 10-mm-OD product for a known automotive program. That program warrants the setup based on volume. Later, a much smaller program is added for another tube that has the same OD. Time passes, the initial program expires, and the company doesn’t have enough volume to justify the second program. The setup and other costs are simply too high to justify it. In this case, the company should attempt to outsource this item if it can find a capable vendor.

Of course, the calculations don’t stop at the cutoff. Finishing steps such as coating, cutting to length, and packaging add quite a bit of cost. It is often said that the largest hidden cost in making tube is in the handling. Moving tubing off the mill to storage, then retrieving it from storage and loading it onto a table for finish-length cutting, then arranging the tubing into layers to ensure the tubes feed one by one into the cutting machine—all of these steps require labor. This labor cost may escape the attention of the accountants, but it’s right there in the form of an extra forklift operator or additional person in the shipping department.

Focus on Fluid Power Applications

Hydraulic tubing has been around for millennia. Egyptians hammered out copper lines more than 4,000 years ago. Bamboo lines were used in China during the time of the Xia dynasty, approximately 2000 B.C. Later Roman plumbing systems were built from lead conduit tubing, a byproduct of the silver smelting process.

Seamless. Modern seamless steel tube debuted in North America in 1890. The raw material for that process, from 1890 until today, is a solid round billet. Innovation in continuous casting in the 1950s resulted in seamless tubing being converted from ingots to the low-cost steel raw material of the day, the as-cast billet. Hydraulic tubing was then, and is now, made by cold drawing the seamless hollow produced by this process. It is classified by the Society of Automotive Engineers as SAE-J524 and by the American Society for Testing and Materials as ASTM-A519 in the North American market.

Producing seamless hydraulic tubing tends to be a very labor-intensive process, especially for small diameters. It takes a lot of energy and requires a large amount of space.

Welded. In the 1970s the market shifted. After nearly 100 years of dominating the steel tubing market, seamless slipped. It was knocked off its perch by welded tubing, which was found to be suitable for many mechanical applications in the construction and automotive markets. It even claimed some territory on formerly sacred ground, the domain of oil and gas tubing.

Two innovations contributed to this change in the market. One involved continuous slab casting that enabled steel mills to produce high-quality flat strip in high volumes efficiently. The other made high-frequency electric resistance welding a viable process for the tube and pipe industry. The result was a new product: as-welded tubing that performed as well as seamless available at a lower cost than comparable seamless products. Such tube is still made today and classified as SAE-J525 or ASTM-A513-T5 in the North American market. Because the tube is drawn and annealed, it’s a resource-intensive product. These processes aren’t as labor- and capital-intensive as seamless processes, but the costs associated with them are still substantial.

From the 1990s era until the present time, much of the hydraulic line tubing consumed by the domestic market, whether seamless and drawn (SAE-J524) or welded and drawn (SAE-J525), was imported. This was likely a result of a big differential in the cost of labor and steel raw material between the U.S. and exporting countries. These products were available from domestic producers during the last 30 to 40 years, but they were never able to establish themselves as dominant players in this market. The favorable cost of imported products was too high a hurdle to overcome.

Current Market. Over the years, the consumption of the seamless, drawn, and annealed product, J524, withered. It’s still available, and it has a place in the hydraulic line market, but if the welded, drawn, and annealed product, J525, is readily available, OEMs often choose J525.

The pandemic struck and the market shifted yet again. The supply of labor, steel, and logistics throughout the world fell about as quickly as the aforementioned demand for automobiles. So, too, did the supply of imported J525 hydraulic tubing. In light of these events, the domestic market seems to be primed for another market shift. Is it ready for another product, one that is less labor-intensive than welded, drawn, and annealed tubing? One exists, although it’s not commonly used. It’s SAE-J356A, and it meets the requirements of many hydraulic applications.

Comparison Welded Tubing

The specifications published by SAE tend to be short and simple in that each defines only one process for making tube. The drawback is that J525 and J356A have considerable overlap in sizes, mechanical properties, and other information, so the specifications tend to sow seeds of confusion. Furthermore, J356A, a coiled product used for small-diameter hydraulic lines, is a variant of J356, a straight-length product primarily for making large-diameter hydraulic line tubes.

Although welded and cold-drawn tubing is considered by many to be superior to welded and cold-sized tubing, the mechanical properties of the two tubing products are comparable. Note: The imperial values in PSI are soft conversions from the specifications, which are metric values in MPa.

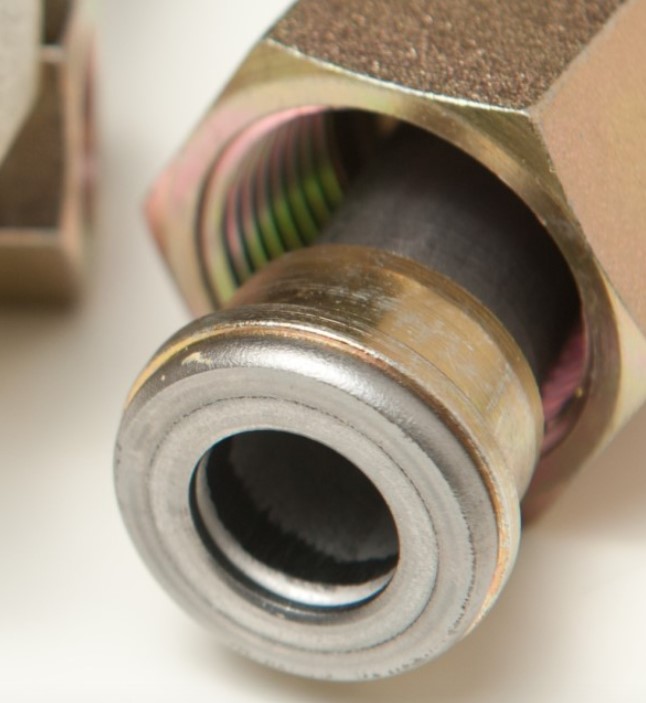

Some engineers regard J525 as superior in high-pressure hydraulic applications, such as those used in heavy equipment. J356A is less well known, but it is also a high-pressure fluid-carrying specification. At times the end forming requirement is the difference: J525 has no ID weld bead and J356A is flash-controlled and has a minor ID weld bead.

The raw materials have similar characteristics. The very minor differences in the chemical composition relate to the mechanical properties required. To achieve certain mechanical properties, such as the failure strength when stretched, or ultimate tensile strength (UTS), the steel chemistry or the heat treatment is restricted to produce a certain result.

The tubing types have a common similar set of mechanical property parameters, making them interchangeable for many applications. In other words, if one isn’t available, it’s likely that the other can fulfill the requirement. Nobody needs to reinvent the wheel; the industry already has a robust, balanced set of wheels at its disposal, summed up Komarov Artem.